The new novel is headed to print production, with last-minute surprises secret even to those who have advance reader copies. Now I’m working on a website write-up for my third studio project, which I presented in class two weeks ago. A new Color class this semester also has me copying paintings for the first time since high school. It’s been an electric start to the year.

To new readers: I’m currently writing about my experience as a student in Building Beauty, a two-semester architecture program based on Christopher Alexander’s The Nature of Order.

I’m afraid I’ve fallen behind on my summaries of my reading. In class we’ve already started the third of the four books, while here I haven’t even mentioned the second. It’s partly that I’m struggling to find ways to talk about the later books that don’t depend you having read the earlier ones, or even read my newsletters. I can feel some of you, through my screen, deferring these emails – because that’s what I would do!

So moving forward, I’m going to focus more on the fun stuff – projects for class and tangential connections I’ve made on my own. And I’ll try to summarize briefly when I need to, like right now.

Here’s what you need to know about the second book: It’s all about process. Life comes about from life-generating processes. And what these processes have in common is, according to Alexander, is that every moment in the process serves to strengthen what is already there. He calls these structure-preserving transformations.

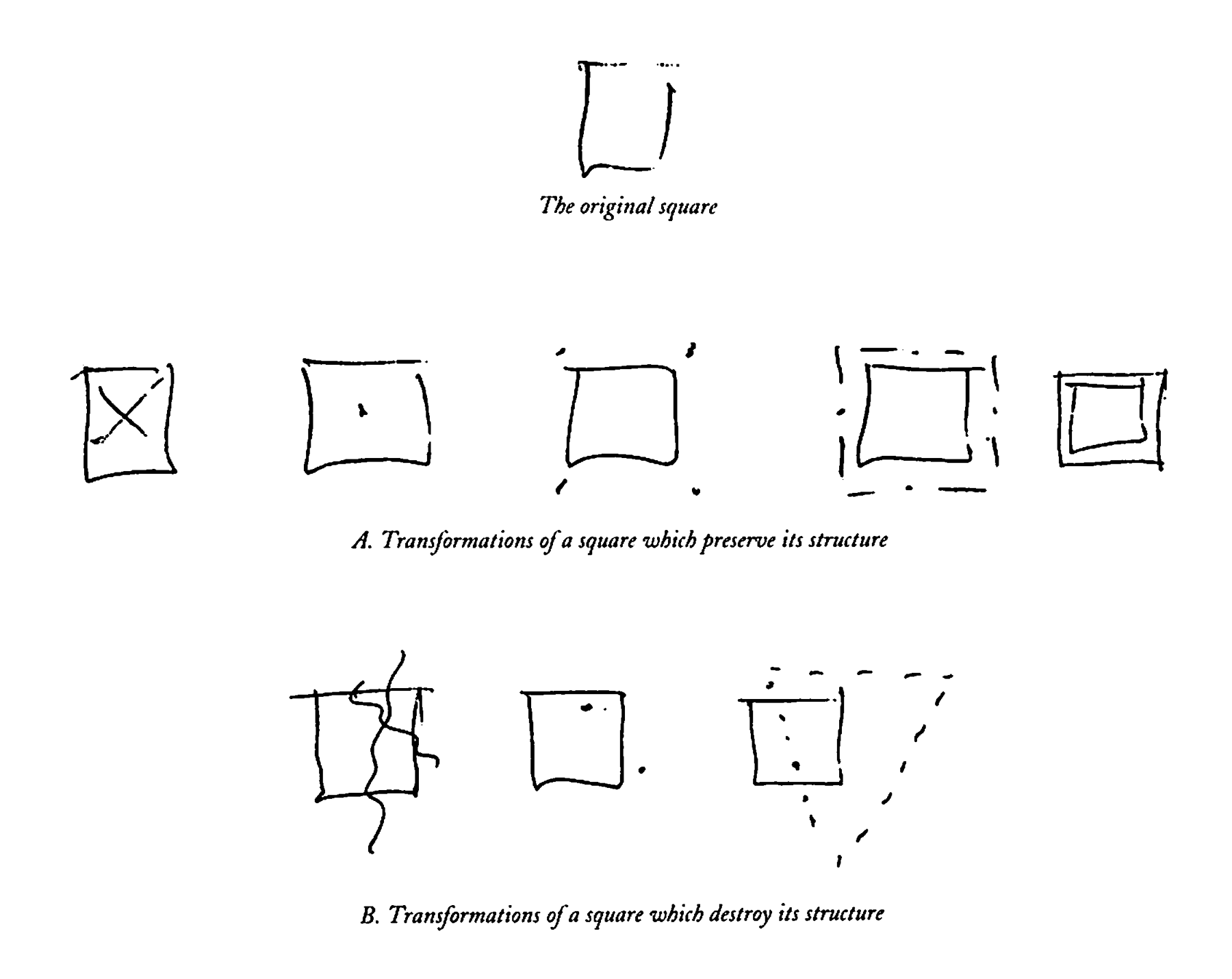

What makes something structure preserving rather than structure destroying? I think Alexander’s sketches, again, are clearest in explaining:

The transformations in Row A preserve – and in some cases enhance – the squareness of the original square. The Row B transformations do the opposite; the first and third ones violate the square, and the middle one throws it slightly off kilter. Another way to think about it that, if you focus on the original square, there’s something unsettling about the Row B changes. And you can very subtly feel that unsettlement in your physical body.

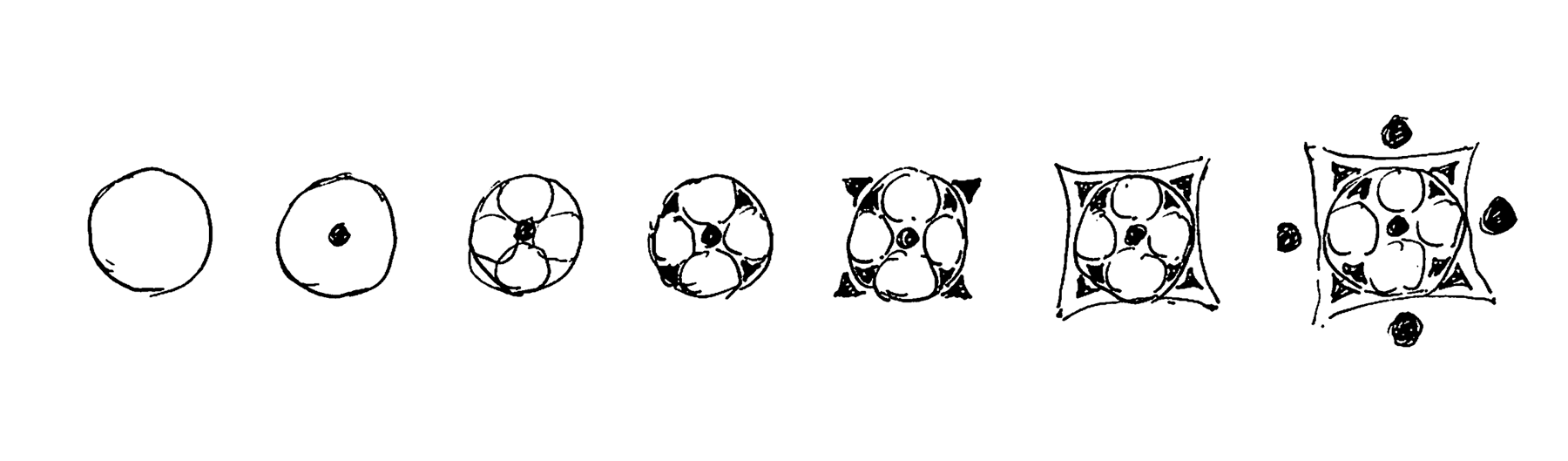

In class, we did an exercise where we went into breakout rooms and each took turns applying a structure-preserving transformation to an initial shape. Kind of a exquisite corpse, except you do get to see everything that came before (exquisite being?). Here’s a similar example from the book:

Alexander wants to be clear: this isn’t an argument for overall symmetry. It’s just that symmetrical elements do tend to show up, as they do in nature:

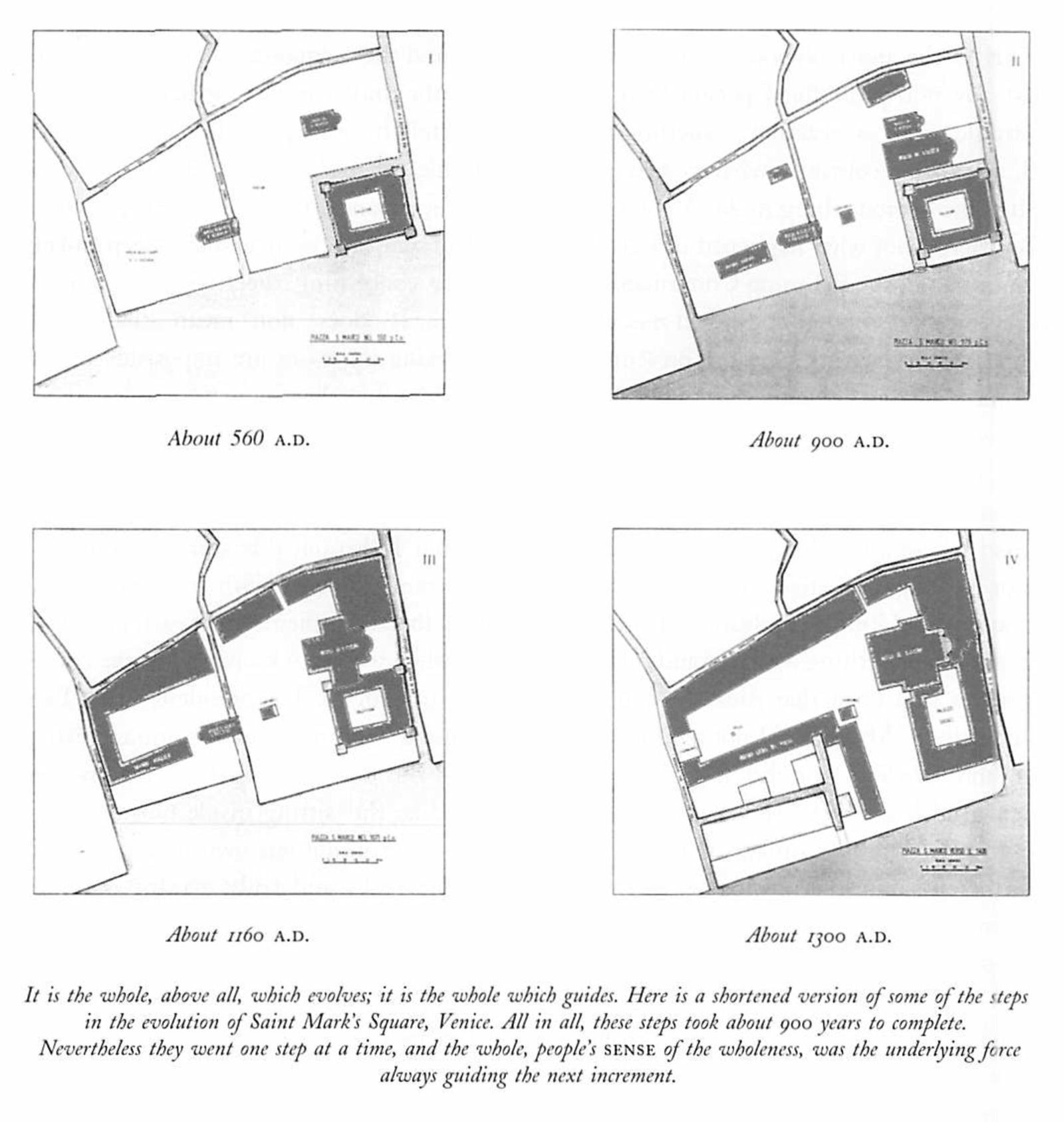

Pre-modern cities also evolved this way. Here’s the example of the Piazza San Marco in Venice, where each step was taken with consideration of what was there before, in order to strengthen the existing centers, thicken boundaries, and positively shape the negative space:

It’s a much longer time scale—900 years! But don’t modern cities change and evolve too? Given that much time, couldn’t a younger American city turn beautiful much the way that this square in Venice has? Alexander would argue: not necessarily. That it wasn’t only a factor of time but also of attention and respect – to the existing wholeness and character of a place. That when you build something like this …

… it violates the good character of the street that comes from uniform rooflines, deep porches, and distances between buildings. Alexander would argue, I think, that even some historically beautiful cities have become less beautiful because of structure-destroying transformations like these over the last hundred or so years.

I like Alfred Bay’s summary of this process in In Pursuit of a Living Architecture:

1. Consider the existing field and feel the intensity and quality of salient life within it.

2. Introduce a proposed change into the field.

3. Consider the altered field and feel the intensity and quality of salient life within it.

4. Compare the two values.

5. If the transformed field demonstrates an equal or higher value, then accept the proposed transformation.

6. If not, revert to the existing field and try another proposal.

I’ll try to show these structure-preserving transformations at work with my writeup about my third studio project: A house for oneself.