I’m currently writing about my experience as a student in Building Beauty, a two-semester architecture program based on Christopher Alexander’s The Nature of Order.

Weeks 6 and 7. I’m jumping back from my previous letter about wholeness and centers a bit, because even before Christopher Alexander really gets into that conception in The Nature of Order, he shows you a series of images side-by-side, and asks, “Which has more life?”

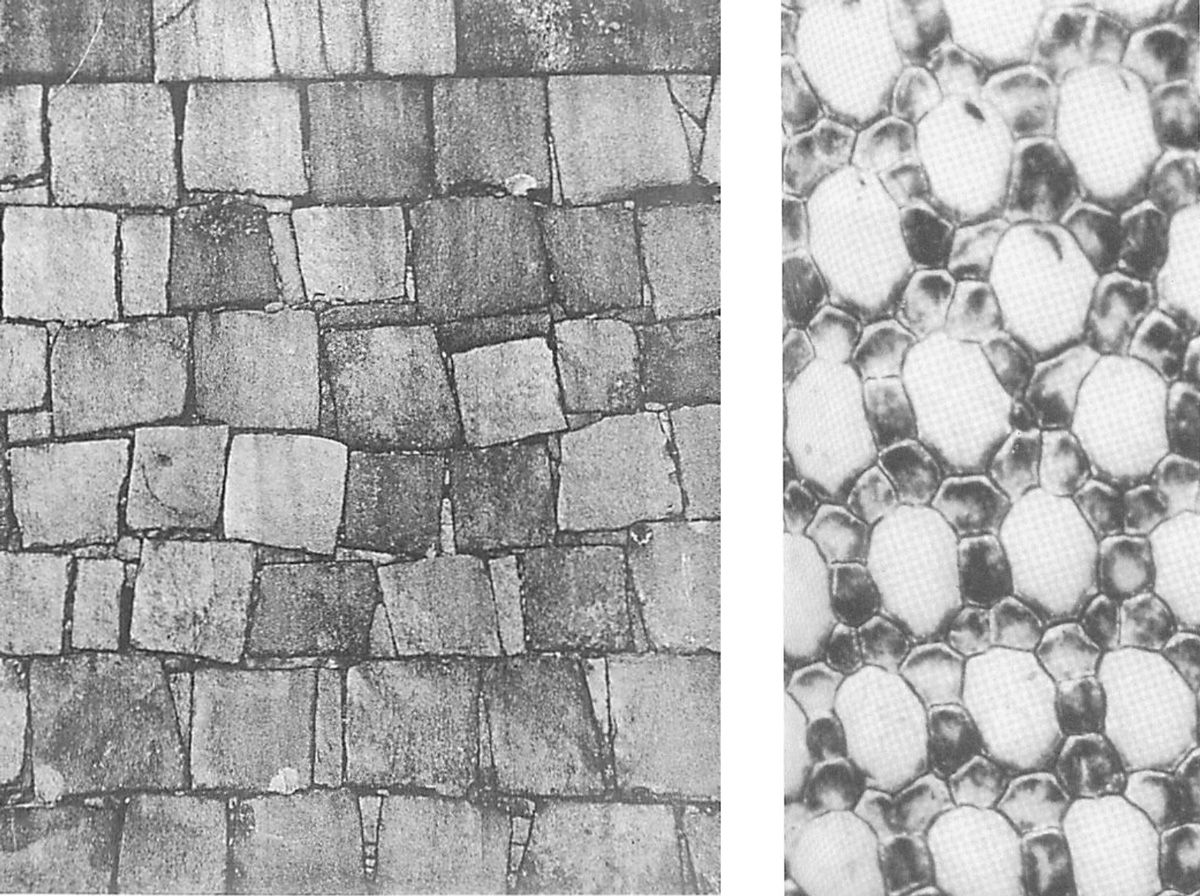

For instance, look at these two images and ask that question:

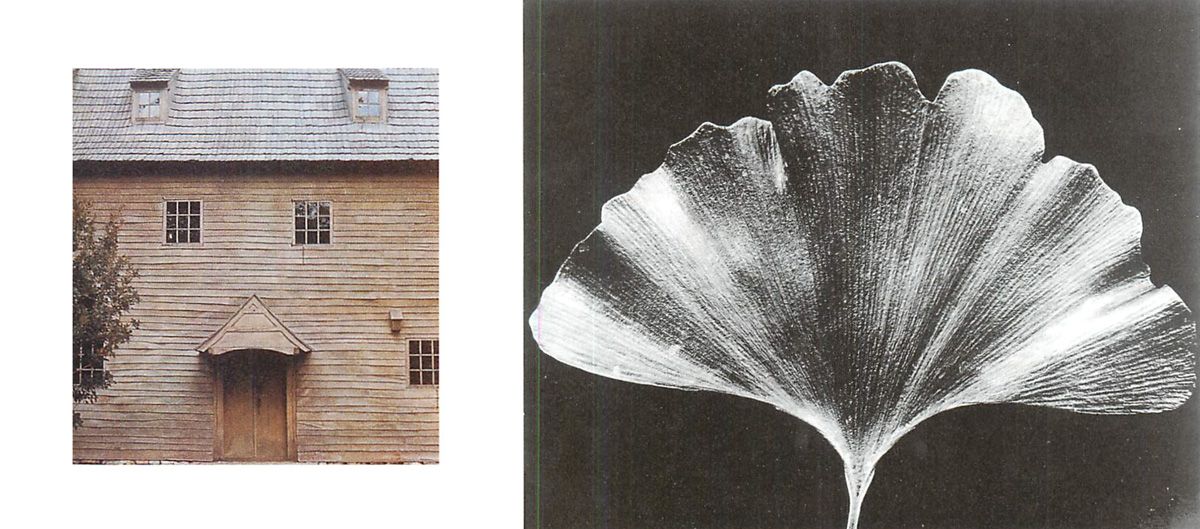

And you’d likely say that the scene on the left has more life to it. Here’s another, slightly less obvious:

If you ask which of the two more stirs something deep within you, makes you come more alive, I’d guess – and Alexander would as well – that you’d again pick the left image. Maybe the quality comes from the more irregular cars, he says, or the way the small kiosk crosses into the space.

Alexander takes you through this series of these A-B tests of the heart and demonstrates how it’s not necessarily how much organic life or greenery is present, not necessarily how old or new the place is, not how modern or traditional, not how wealthy or impoverished, not even how much detail or ornamentation is present.

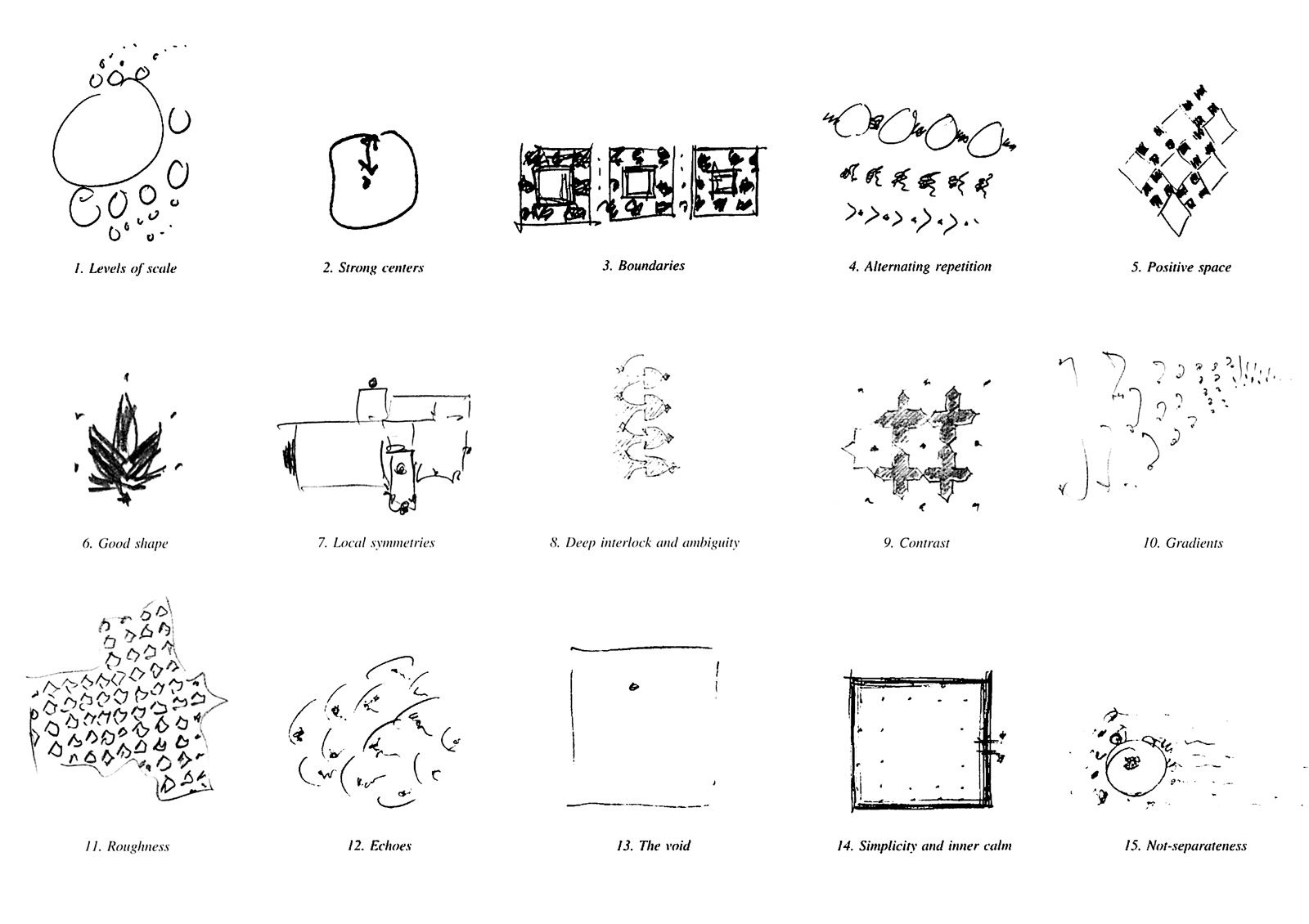

So then what is it? Alexander (who was a mathematician before he was an architect) spent years – decades – doing these side-by-side comparisons, looking for images, objects, and spaces that he felt to have more life, trying to figure out what they had in common. From this he derived fifteen(ish) fundamental properties (“The precise number fifteen is not significant. But I do believe that the order of magnitude of the number is significant”).

It’s hard to explain properties these in a pithy way because they’re the meat of the first book and we spent three weeks in class going over them. I’ll admit that there are a few that I still don’t fully grok, or aren’t fully convinced are separate properties. But I’ll try to summarize.

1. Levels of Scale. Every level of scale, every order of magnitude is present. A tree has branches, leaves, veins in leaves, and so on. The kinds of modern architecture that we think of as cold and lifeless often skips over levels of scale – think: large slabs of concrete with tiny untrimmed windows.

2. Strong Centers. Centers are intensified by other centers that point toward it. An ornate frame that concentrates your attention on a Van Gogh painting; a sequence of smaller rooms leading to a sitting area.

3. Boundaries. Namely, thick boundaries that are a similar level of scale as the centers they bound. In nature a river might have a wide, silted bank. Windows with wide trim, deep reveals, shutters along the sides – boundaries that are as big as the window itself.

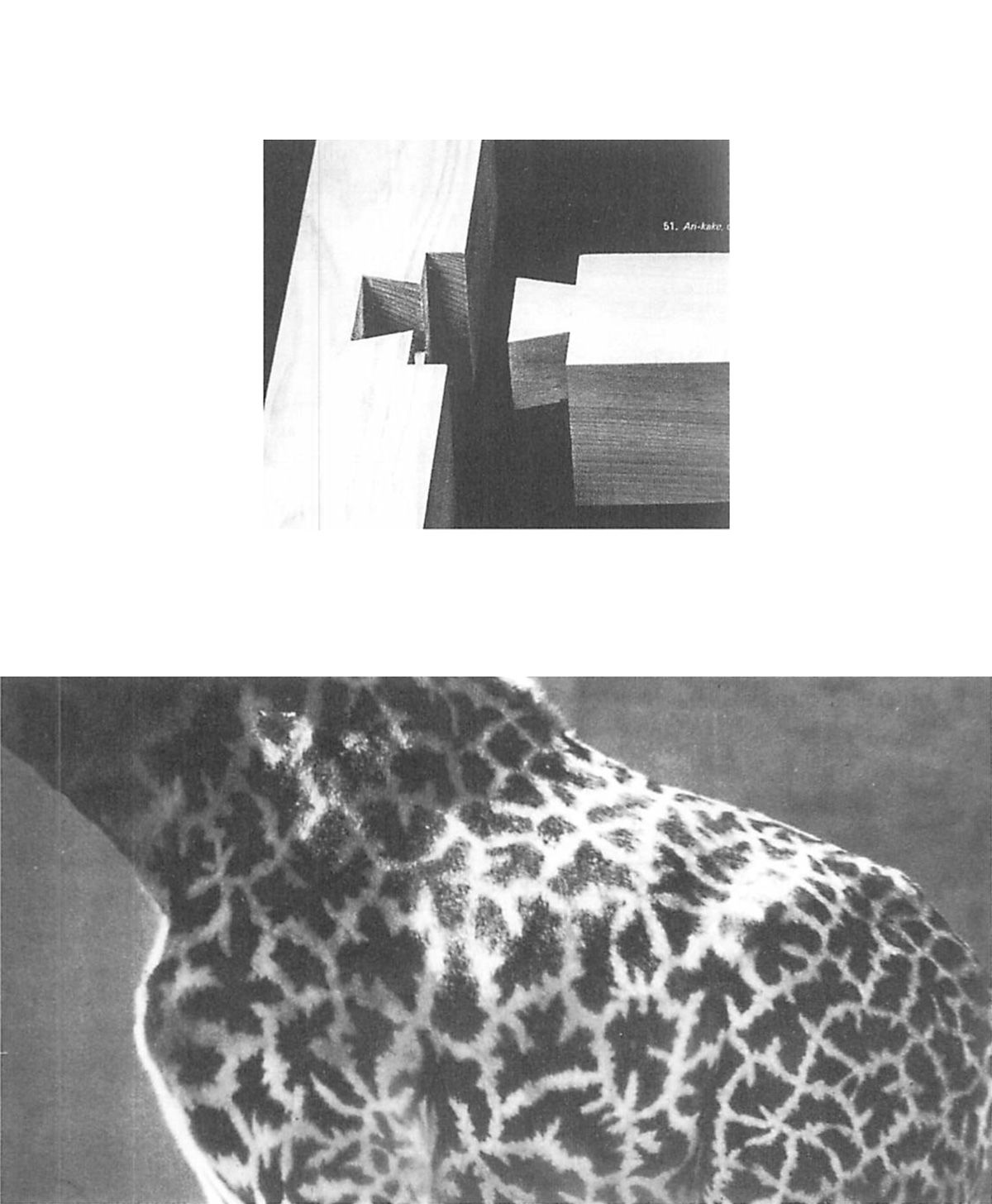

4. Alternating Repetition. When the rhythm of repeated centers are intensified by a second set of repeating centers, often coming out of the negative space between the first. The space between the leaves of a tree. Or the various arrays of motifs on a carpet.

5. Positive Space. Here I think of the way that type designers pay attention to the negative space around the letterforms, or the optical illusion that shows both a face and a vase. Negative space, when as well-formed as the center it surrounds, becomes positive. There are no “leftovers”.

6. Good Shape. According to Alexander, “It is easiest to understand good shape as a recursive rule […] the elements of any good shape are good shapes themselves.” But honestly, this feels like a know-it-when-you-see-it kind of thing.

7. Local Symmetries. Not to be confused with perfect symmetry, where something is just a mirror image of itself. Things in nature, like the human face, are never perfectly symmetrical. My take is that this has to do with smaller symmetrical centers making larger, asymmetrical ones more coherent. Tables and chairs not in the middle of the room but in their appropriate spot. Rectangular rooms not just in a bigger house-rectangle but fitted around an outdoor space.

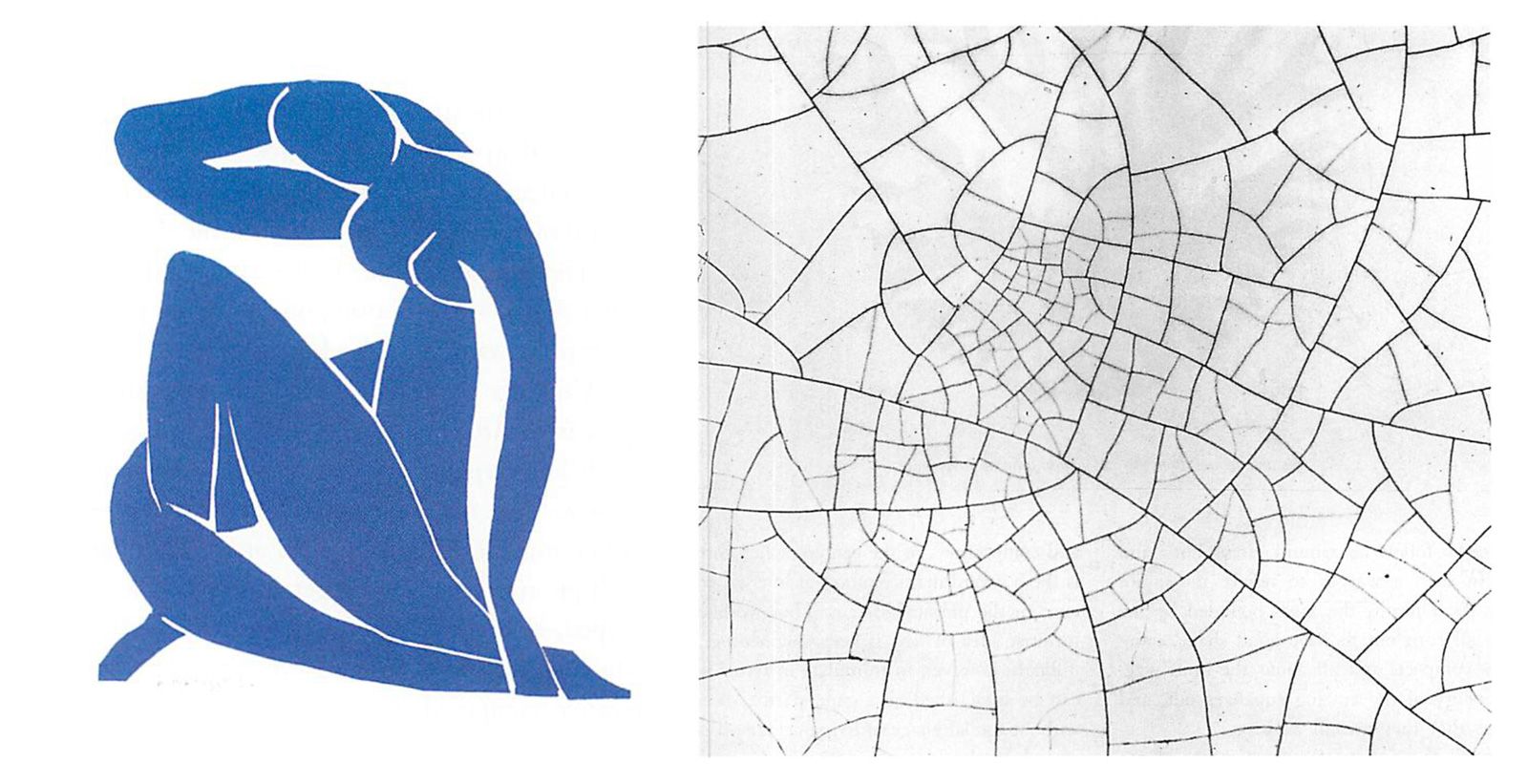

8. Deep Interlock and Ambiguity. Centers that knit together larger adjacent centers to such a degree that you can’t tell which they belong to.

9. Contrast. Not just visual or textural contrast, but contrast that strengthens and unifies, instead of separates. “The awareness of silence created by a hand-clap.”

10. Gradients. At first this seems to go against the previous property, but it feels less about a gradation of light or color than it is about transitions to do with the real physical world. The edges of a cloud are whispier than the core. A building’s lower timbers can get thinner going up, because they don’t need to support as much weight.

11. Roughness. Not necessarily textural roughness or patina, but roughness in the sense of fitting to context, odd corners, uneven terrain and materials. As if grown into place.

12. Echoes. Sharing the same forms and angles, feeling as if from the same family. In nature, small rocks echo the mountain; atomic motion echoes the galactic motion. This echoing seems most visible to me when it happens across levels of scale.

13. The Void. The still center. A feeling of potentiality. It may be a field of solid color in the middle of an ornate rug, or the empty table on which meals occur. The calm surface of a pond.

14. Simplicity and Inner Calm. What you get when you strip away all the unnecessary centers. Not to the extreme – not minimalism the way that you might think of it here in the early 21st century. A sense of humility and ease. Everything in its right place.

15 Non-separateness. Maybe the most important property, according to Alexander. A feeling of being totally connected to the world, totally a part of it. Full integration. The epitome of nature. “You cannot really tell where one thing breaks off and the next begins, because the thing is smokily drawn.”

You might’ve noticed how the properties are related to each other, and often overlap and interact. The key thing to remember about them is that they aren’t ingredients to a recipe. You don’t put them in your design one at a time and automatically end up with something that feels alive. To see them as parts to be assembled is exactly the mechanistic worldview that Alexander’s railing against.

I think of them more like trace residue – when you create something brimming with life, it will tend to exhibit these properties. That said, you can use them as a guide, a debugging tool, for when you’re struggling with your design. I compare it to the way that when a story I’m writing isn’t working, it can be helpful to step away from the text and write out character arcs and motivations, outline scenes and sequences and heroes’ journeys.

A far better, more essential equipment in the making process, is your own instinct. It’s a knife that’s sharpened over time, through an elaboration of the side-by-side test that Alexander starts his discussion of the fifteen properties with. He calls it the Mirror of the Self. More on that next time.