I’m currently writing about my experience as a student in Building Beauty, a two-semester architecture program based on Christopher Alexander’s The Nature of Order.

It’s my last week of class. Monday morning we had our final Studio presentations and I finished my prep a bit early, and spent some time cleaning my workspace, reordering the end-of-project entropy.

A big lesson for me over the course of the, um, course, is that it’s not only that the messy parts of the process beget a messy workspace, but that it goes the other way around, too. That there’s a more-than-practical reason French chefs (or my mom) keep their kitchen prep areas perpetually tidy. That you respond physically, viscerally, to beautiful and life-sustaining environments, and that even temporary changes to those environments – like having a mess of glue and modeling materials strewn across a cutting mat – dampens your sensitivity to beauty, your ability to make full-bodied judgments.

This intersects with a topic that’s come up again and again in lectures and readings around the main text for the class: Architecture’s relationship to care and maintenance. Guest lecturer Dil Green speaks about care and reciprocity, how a building or space that feels beautiful or alive shows an overcommitment; that enough people cared about it, and this care resonates inside of us and encourages us to care:

We feel that there is an offer of reciprocity there, that if we respond to the care that’s been put into that building, we will in turn receive something […] Those buildings have the life-like quality that they get to persist against the decay of time because we care for them.

Later, Green talks about the difference between care and cleverness:

Care is regenerative. If you care for someone and you put care into a system, it becomes more capable of caring for you. Cleverness, though, is always extractive. Cleverness looks at a situation, goes away, and thinks, “Aha! I’ve made a new idea out of that.” It’s taken something away from a system or situation and all it’s come up with is a clever idea.

Repairability, says Green, is a reciprocation of care. A thought experiment I do to suss out genuine repairability is whether or not you’d be able to scavenge the parts and tools to fix something in a post-apocalypse scenario. For most modern phones and laptops, probably not. Desktops with standardized ports and slots, a bit more likely. Goodyear-welted (or hand-welted) boots, even more likely. That’s not to say that I myself would necessarily be able to. More that the ability to do so is not locked into a clever but largely closed infrastructure.

Speaking of infrastructure, this piece by Derek Thompson on the “Eureka” Myth revolves around a brilliant metaphor by economic historian Joel Mokyr: Infrastructure as the embodiment of invention.

I also enjoyed (and need to re-read) this expansive essay by Shannon Mattern on maintenance and care, “A working guide to the repair of rust, dust, cracks, and corrupted code in our cities, our homes, and our social relations.”

Here’s David Abram in The Spell of the Sensuous quoting the anthropologist Helen Payne:

The maintenance of a site requires both physical caring (rubbing of rocks or clearing of debris) and the performance of ritual items aimed at caring for the spirit housed at it. Without these maintenance processes the site remains, but is said to lose the spirit held within. It is then said to die. And all those who share physical features and spiritual connections with it are then also thought to die. Thus to endure the well-being of life, sites must be cared for and rites performed, to keep alive the dreaming powers entrapped within them.

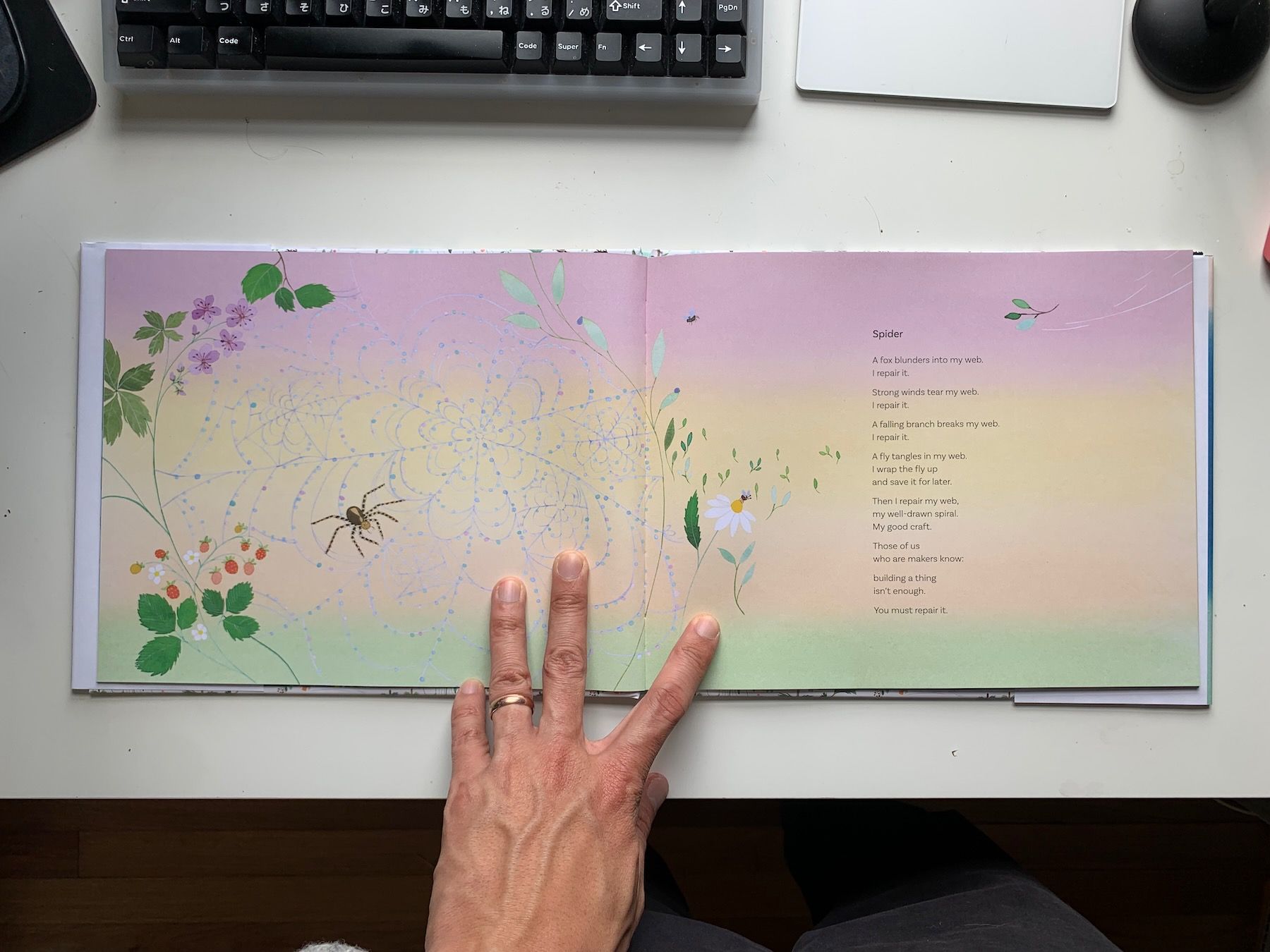

And my favorite spread in my favorite picture book that I’ve read so far this year, Kate Coombs’s Today I Am a River, illustrated by Anna Emilia Laitinen:

Finally, a line I heard from my classmate Aarti, attributed her teacher, the late Munishwar Nath Ashish Ganju, an architect and educator (and former Building Beauty faculty):

The only thing that needs no maintenance is a coffin.

Keep on mending, friends.

p.s. Registrations recently opened for the 2023–24 academic year of Building Beauty, in case you’re curious about doing what I been doing these past eight months.