Our final studio project for Building Beauty was to build something within our community, with community defined as “you and at least one other person.” It could be a spouse or roommate, it could be the students, staff, and families of a Montessori school, it could be the customers of a blueberry farm, etc. From the assignment:

The main emphasis is to try to create something real and positive in the world – something that will make your particular community a better place in some way.

I chose, as my community of focus, my own neighborhood in Detroit.

1. Site Analysis and 1:200 Model

As with the previous studio projects, our first step was to better understand the greater context, and particularly its key centers – the aspects that give it its overall vibe or wholeness. In my case, the strong centers included a couple of nearby parks, a grocery store, and a cafe, but also the old houses themselves, and the locust trees poised over the main boulevard.

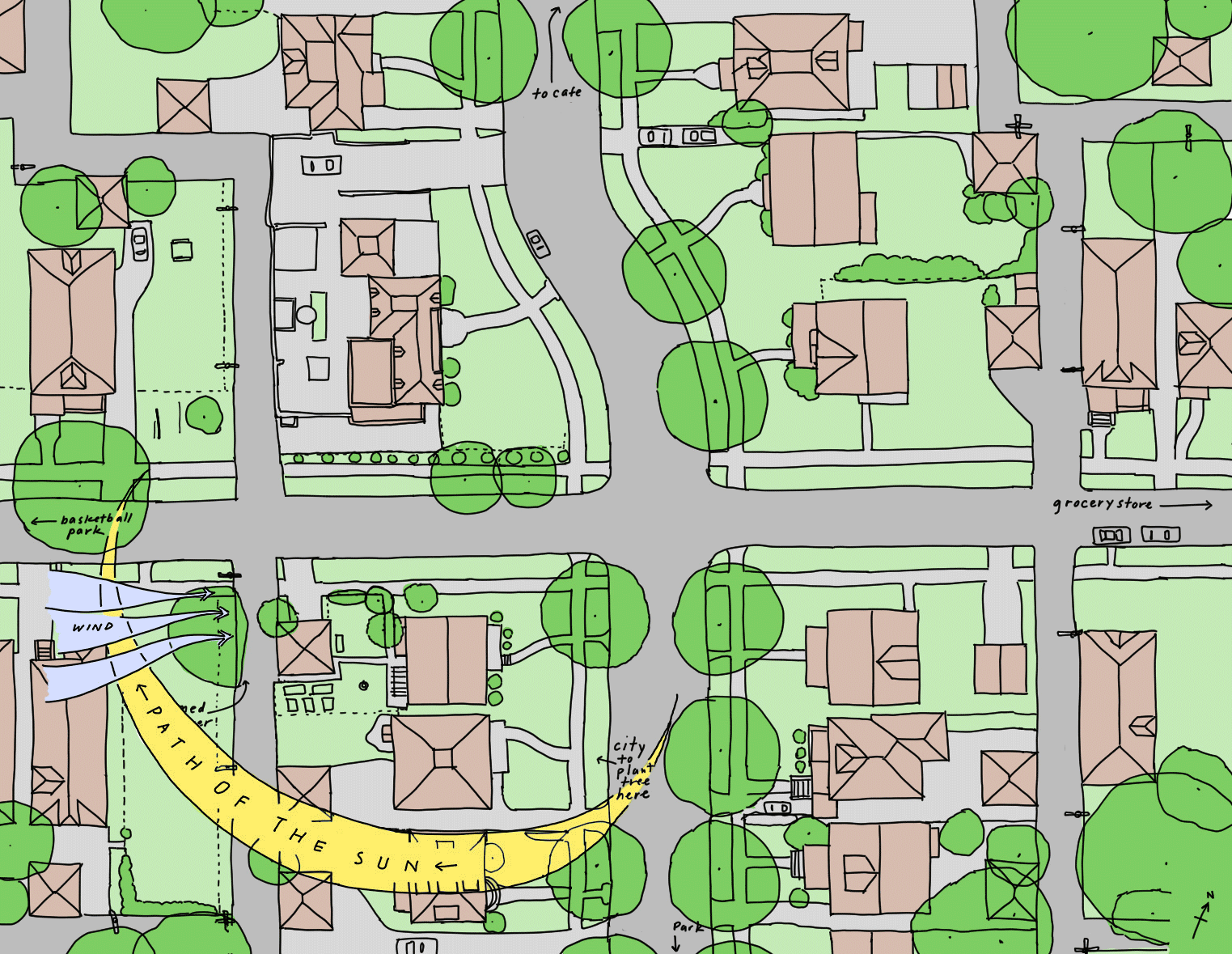

Like in the dream house project, I drew up a site map (I’ve removed the street names and labels to make it slightly less findable):

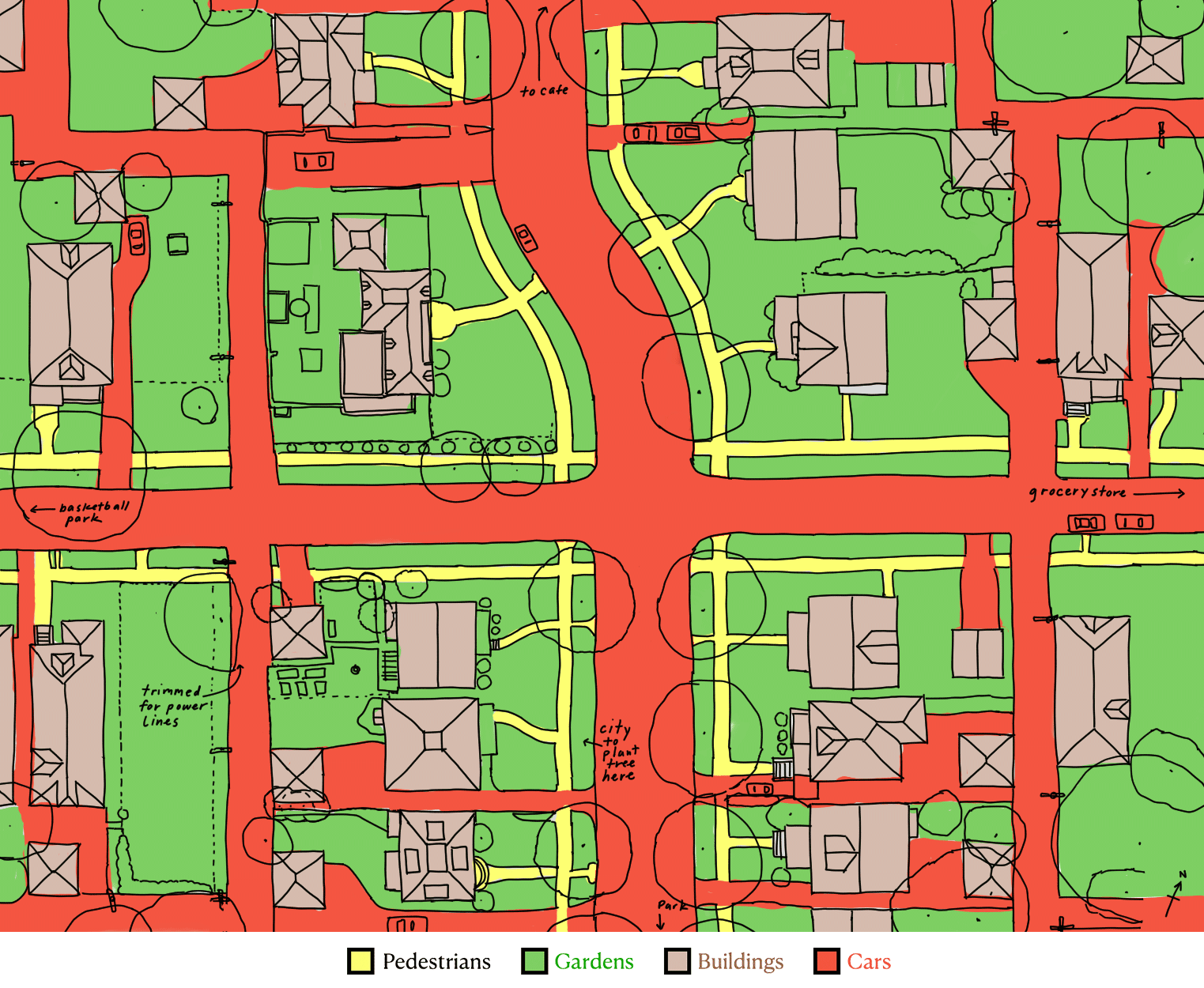

I played around with a couple different ways of color-coding it. The below version, based on maps that Christopher Alexander and his team created for the Progresso district in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, is particularly revealing:

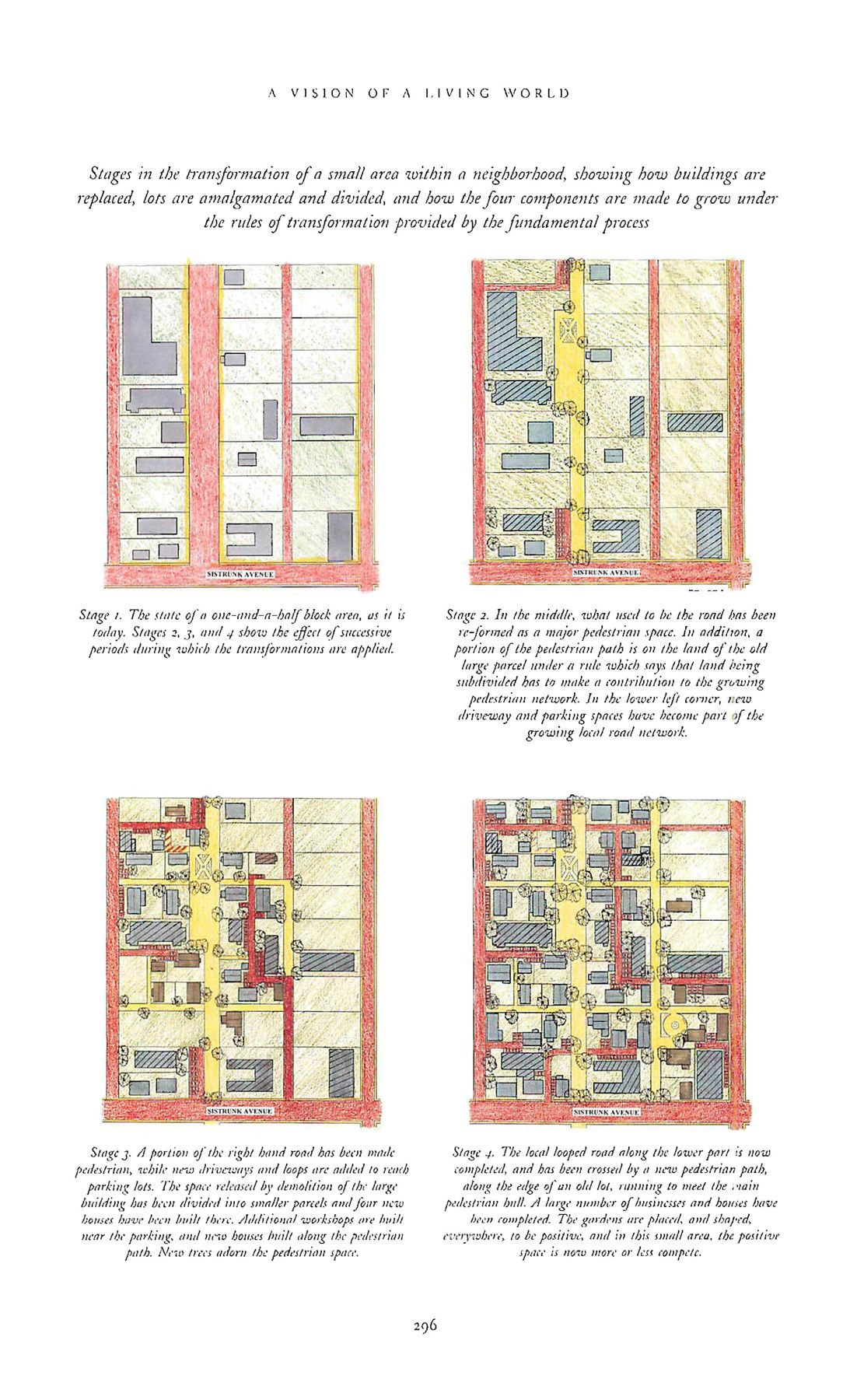

You can see, from all that red, how much space is devoted to cars. The movement of cars, the parking of cars. Cars, cars, cars! For the Fort Lauderdale proposal, Alexander and co. actually came up with a set of moves – changes to zoning and building codes, etc. – that would, over time, nudge the neighborhood to a more beautiful, person-scaled one. I find this page about the project, from the third Nature of Order book, remarkable:

We’re seeing this more and more in American cities, streets closing to car traffic and going pedestrian-only. Sometimes a temporary closure works out so well that it becomes permanent, as has happened in here both in Detroit and Ann Arbor. But looking at these maps – from 1996! – those interventions seem like only an iceberg-tip. A sad epilogue to Alexander’s Fort Lauderdale project is that the proposals were never adopted by the city.

Back to the present day. I expanded my site map’s coverage area when I made my 1:200 model – so as to encompass more houses and a full neighborhood block:

What I got an even stronger sense of, looking at this model and discussing it with everyone in class, was the stark difference between the very public streets and sidewalks, and the very private houses, set back like fortresses on deep front lawns:

So we have extreme degrees of public and private, with little in between, and most of that public space is devoted to cars. In short, it’s a typical American neighborhood.

2. Community Interviews

While I worked on these maps and models, I was also conducting one-on-one interviews with my neighbors. I put out a request on our block club’s group chat, and also contacted a few others directly. If I were doing this in, say, some official city planning capacity, I would go door-to-door and make sure that I talked to as many residents as I could. But given that I only had a couple weeks to do the interviews, I basically just tried to fit in whoever agreed to do one.

All in all, I spoke to about a dozen people. A classmate interviewed me as a warmup, and so my own perspective is included, as is my partner Julia’s – we are a part of this community too! It was important for these interviews to be one-on-one because I had to get at each individual’s personal, intimate dreams and visions – harder to do in group situations where strongest voices tend to dominate.

In fact, it was less of an interview and more of a guided meditation. I’d ask people to close their eyes, if they felt comfortable doing so, and we would walk through a scenario in their dream neighborhood, me asking questions along the way to draw out sensory details – what they see and hear, the textures under their feet – so that I could clarify, in my own mind’s eye, what they were noticing in theirs.

One thing of note: I asked interviewees about their dream neighborhood, but not necessarily their dream version of ours. Their dream neighborhoods inevitably had some of the existing neighborhood in it, like the main boulevard’s locust tree coverage and our unique 1920s era houses. But it was important for this exercise to not get mired in feasibility concerns, to not limit their imaginations. One way I framed it was to say: You’re constrained by physics, but not by politics.

Typical city planning feedback sessions involve getting a community all in the same room. I’ve participated in a few myself and have voted with sticky notes for streetscape designs, and listened to neighbors raise concerns after a presentation by a developer or planning team. There’s a place for those forms of participation, but I think this kind of “visionary interviewing” is even more important. It’s the difference between asking someone for comments and asking them to write fiction.

With permission, I recorded each interview on my phone’s Voice Memos app. Then at home I popped the audio file into Good Tape, a nifty transcription service aimed at journalists. I re-read the transcribed interviews and tried to identify common themes and patterns, which resulted in …

3. A Project Pattern Language

Christopher Alexander is best known for A Pattern Language, a collection of design patterns for beautiful space, from a planetary scale all the way down to the small personal items on your dresser or bookshelf. Many readers see the book as a kit-of-parts; just pick the right combination for your own project and you’re all set.

But the book is called A Pattern Language, not The Pattern Language. Alexander stressed repeatedly that every project requires its own unique pattern language. Now, there may be overlap between a project language and the book’s Esperanto, but each place and community has patterns unique to that context. A Pattern Language isn’t supposed to replace discovery. Hence: interviews!

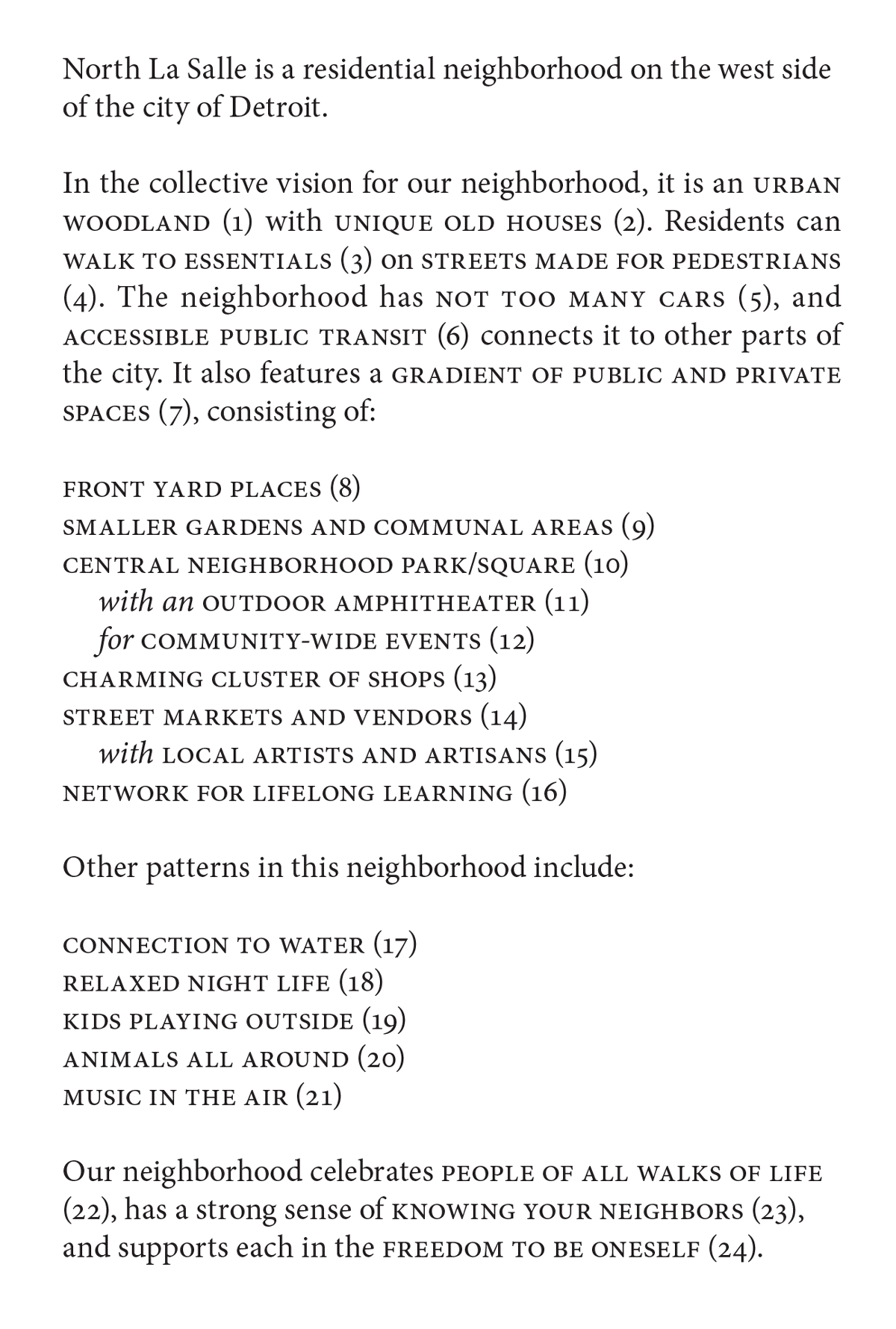

After combing through, I identified two dozen patterns that together formed a collective vision of the neighborhood (again, as collective and representative as a dozen mostly-friends on a limited time scale can be). Here’s my table of contents, patterns strung together in prose:

Sound like a nice place to live? I think so! In synthesizing the patterns, I also adapted them to work with our existing neighborhood – or at least an idealized, maybe-decades-in-the-future version of it.

For example, some interviewees saw themselves, in the visualization exercise, living at the edge of a large lake. But we don’t have even a small pond in our main park. So I translated that desire into a more general pattern titled CONNECTION TO WATER (17):

17 CONNECTION TO WATER

There is always water close by. Larger bodies of water are reachable by bike or ACCESSIBLE PUBLIC TRANSIT (6), and parks have natural or manmade ponds and fountains. FRONT YARD PLACES (8) have their own water features. The neighborhood has a few swimming pools.

For each pattern, I pulled three or four quotes from my interviewees (names hidden for privacy’s sake):

Water and light.

Some kind of natural water, maybe a pond ... but just the sound of trickling water.

You don’t necessarily need it to happen right near your home. You want to be able to get to it ... if you even decide you want to take a bike ride there, you could do it ... There’s a beach, a nice huge body of water. Who doesn’t like to be off the water and the shore and to see nice things like that?

There’s some closeness of water ... some sense of, I could get to the water if I needed to.

But what about when there were conflicting visions? Some people, for instance, envisioned manicured front lawns, while others saw their yards covered with native plants – no lawn at all. At the same time, everyone did acknowledge that they might have differening tastes and preferences. There was a universal desire, too, for front yards to be well-taken-care of rather than neglected. So this pattern came together FRONT YARD PLACES (8):

8 FRONT YARD PLACES

Front yards, also individual to the UNIQUE OLD HOUSES (2), are functional places in their own right. Some have manicured lawns, others contain lush gardens; they are all well-cared for and beautiful in their own way, and transition between the public street and private house. They serve as outdoor rooms with porches, stoops, and benches – semi-public spaces that add greatly to the sense of KNOWING YOUR NEIGHBORS (23).

I love what this neighbor said in their interview about the yards:

They’re very individualized. Instead of everybody just defaulting to grass, people are planting rain gardens or making it beautiful in their own way. Not everybody has the same aesthetic, but I think everybody wants to be around something that feels good to look at. Walking by, I see my neighbors’ own iterations of what they think is a beautiful front space, and lots of inviting spaces for people to hang out and chat.

This jumped out at me as I was compiling the project language. Remember our model from before?

Those empty front yard are not due to a lack of detail in the model – at least not mostly. Everyone had visions of these varied front yard places, but if you look down the street as it is today, it’s a sea of mowed lawn.

4. What to Build?

Everything so far has been in service of answering the broader question, How do I bring more beauty to my community? Coming in, I had ideas for what I might build. For practical reasons, they were all to do with something in my own home, on my own property.

Doing the interviews and coming up with a community pattern language helped situate those ideas in something greater – and spawned new ideas. I was now asking a more specfic question: What can I do, on my own property, within my own realms of influence, that would take a step toward the collective vision of the neighborhood?

I decided that the most significant move I could make was to turn my own front yard into a FRONT YARD PLACE.

Doing so might inspire my neighbors to do more of the same. At the very least it could, like the interviews themselves, start conversations about our dreams for the neighborhood.

I started playing around with designs on the 1:200 model using construction paper and cardboard, kind of like doodling designs for a carpet:

Which was fun and all but also overwhelming, like I had too many options and not enough helpful constraints. I felt a bit lost.

It turned out that while I had this pattern of front yard places for the neighborhood as a whole, I only had a vague idea of my partner Julia and I saw for our own front yard – for our smaller community of two.

5. A Second (Mini) Pattern Language

I went back through our interview transcripts and reread the bits about front yards. I quickly interviewed Julia again, posing scenarios like: Say you’re walking in the neighborhood and turn the corner and see our front yard in the distance, what do you notice about it? Or: What do you see on your way from the sidewalk to the front door? I closed my eyes and tried to imagine walking it myself.

The result was a smaller set of patterns unique to us and our front yard:

SENSUOUS ENTRANCE TRANSITION

WELCOMING SIDEWALK GATEWAY

DEEP, COVERED SITTING PORCH

MULTI-PURPOSE OUTDOOR ROOM

COLORFUL QUILT OF NATIVE PLANTS

COMMUNITY CORNER

Some of them are evident from the title, but to elaborate on one that might not be:

COMMUNITY CORNER

A public area of the front yard acts as a mini plaza of sorts. A bench invites those walking by to sit and take a break on the way to/from the park or grocery store. A Little Free Library and pantry hold books, vegetable garden surpluses, and other donations; a covered notice board displays flyers for community events, lost pets, and cards for local artists and businesses.

Our house is on a corner lot. Not only is it on a corner lot, it’s also at a bend in the boulevard. We’ll see people walking to and from grocery store to the east, and to and from the smaller and larger parks to the west and south. The bend in the boulevard also makes it a natural stopping point: I’ve noticed people stopping to tie their shoe or check a stroller, stopping to down set their grocery bags and catch their breath. It’s a special corner, and beckoned special treatment.

I went back to my model and started trying out designs with the same construction paper, cardboard, and foam, this time with a much clearer sense of the community corner and other patterns — the other centers – important to our front yard.

You can see the results in Part 2.

Bonus: I Made a Zine

The course ended in May, but while it was still happening I went to a Risograph orientation at Small Works, a local print shop. My main intent, along with just learning how to use the Riso, was to eventually print a paper zine of the community pattern language to give to my neighbors.

A few weeks ago, I went in and did just that:

Then I biked around on a sunny afternoon, happily sliding copies into interviewees’ mail slots. We’ll be hosting a gathering at our home soon so everyone can talk about the results together, and see the model for the neighborhood and the more detailed one for our own front yard – again, coming in part two!